Chapter 2 What is web accessibility?

The power of the Web is in its universality. Access by everyone regardless of disability is an essential aspect.

This quote by Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web (www), is used quite often in the accessibility community. And I believe it is a very fitting quote to start this course with.

Accessibility is an essential aspect of the Web’s universality. Access by everyone regardless of disability is what makes the Web accessible. If it’s not accessible, the Web isn’t truly universal. The Web literally wouldn’t be what it was meant to be if it’s not accessible!

On the Web, accessibility has a very specific meaning. And in order to design and develop accessible digital products, we need to clearly define what makes a product accessible.

In this chapter, we’re going to define what web accessibility exactly is. This definition will guide every design and development decision you will make as you endeavour to create more accessible websites and applications.

We’re also going to discuss the difference between accessibility, inclusivity (or inclusive design), and usability in the context of the web.

Understanding the difference between accessibility, inclusivity, and usability on the web is sometimes critical in guiding some of your design decisions, as well as determining which approach or strategy you may want to use in your development process.

Understanding how accessibility is different from usability will also help you understand what accessibility specialists usually mean when they say that accessibility compliance is not enough, and that you should aim for usability to ensure that your work is truly accessible.

And finally, since there is no accessibility without disability, we’re going to talk about the different kinds of disabilities, and the different ways people with disabilities access the Web, including various types of assistive technologies.

So, let’s dive in!

What is Web accessibility?

In its strictest definition, the word “accessibility” means “the quality of being able to be reached or entered”. It refers to the ability to access information or systems.

In the context of the Web, however, accessibility has a more specific meaning.

Web accessibility refers to making websites and applications accessible to people with disabilities. It is about removing barriers to access, so that websites and applications can be accessed and used by people with disabilities.

There are many types of barriers that people with disabilities may encounter.

In the physical world, a barrier to access might come in the form of things like:

- Stairs and curbs without ramps (which deny access to people using wheelchairs)

- Narrow sidewalks, doorways, or aisles

- Small toilets and washing facilities without grab bars

- Inaccessible furniture, such as high shelves and tables without leg space

- Low lighting (which makes it hard for people who are deaf to communicate visually)

- Weak colour contrast

- Lack of automatic or push-button doors

On the Web, there are several things you might do that can potentially impede access to information for people with disabilities. Digital barriers to access can take many forms, including but not limited to:

- Absence of keyboard focus indicators

- Absence of labels on form controls

- Buttons, links and UI widgets that can’t be operated with a keyboard

- Images without alternative (alt) text

- Videos without captions, transcripts, or audio descriptions

- Low color contrast and small fonts

- And certain types of motion and animations that can’t be paused or stopped

Throughout the course, we’ll tackle various kinds of barriers and learn how to avoid them, as well as fix existing barriers in your projects.

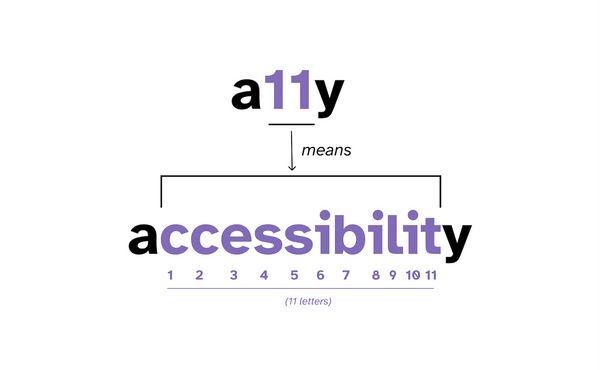

What is a11y?

Accessibility is often referred to as “a11y” in the web community. If you’re new to accessibility, you may have come across this term already and you may have wondered what it means.

a11y (pronounced A-one-one-Y or A-eleven-Y) is a numeronym of the word “accessibility”. A numeronym is a word that uses numbers to shorten words.

The word accessibility is made of 13 letters. There’s 11 letters between the letter “a” and the letter “y”. So this term was created to shorten the word “accessibility” to “a11y”, with the 11 representing the 11 letters between “a” and “y”.

For many people new to the accessibility world, this term may be unfamiliar. So, like other acronyms or abbreviations, if you’re going to use this abbreviation, a good practice is to spell out the word “accessibility” in full the first time, and follow it with the numeronym that it represents:

Accessibility (a11y)By doing so, you’re making it understandable, which is a requirement of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. (We’ll learn more about the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines in the next chapter.)

The term “a11y” also has the added benefit of looking like the word “ally”, which may or may not have been intentional, but is a welcome similarity.

That being said, if the word “a11y” literally looks like the word “ally”—as in, the letter “l” and the number “1” are indistinguishable—it might be a sign that your chosen typeface may not be very readable for some people. If that’s the case, you may want to choose a different typeface that has easily distinguishable characters so that it is more decipherable by users with visual or cognitive disabilities, such as dyslexic users.

What is the difference between accessibility, inclusivity, and usability in the context of the web?

Accessibility vs Inclusivity on the web

The terms “accessibility” and “inclusivity” (or inclusive web design) are often used interchangeably in the context of the web. But they do mean different things.

Web accessibility design is about ensuring equal access for people with disabilities. It is about removing barriers to access, so that people with disabilities can perceive, understand, navigate, and interact with websites and applications. It addresses issues specifically related to disability, and it does not try to address broader issues.

On the other hand, inclusive web design is about encapsulating a wide range of people from various backgrounds and cultures, ages, abilities and disabilities, genders, geographical locations, languages, computer literacy, and more. It tries to address diverse issues so that all users are involved to the greatest extent possible—and that includes people with disabilities. So inclusive design encompasses accessibility. A product isn’t inclusive if it is not accessible.

Internationalization is an example of an Inclusive Design effort, targeting users speaking different languages—regardless of disability—but it is not specifically an accessibility effort.

Web performance is another example of inclusive design, targeting people on low-end devices or slower internet connections, who might be located anywhere around the world, and who may or may not be living with a disability or living in a situation that limits their ability to access information on the Web.

An inclusive designer is proactive in pursuing inclusion of everyone as much as possible, regardless of ability or disability. An accessibility designer, on the other hand, focuses primarily on the needs of people with disabilities.

A Web accessibility designer would design a website that a person with a disability can use, whether that person is accessing it using a screen reader, a keyboard, a braille display, switch controls, or any other form of input modality or assistive technology. For example, someone using a screen reader or those who navigate the Web using a keyboard should be able to carry out the same tasks on a website as someone without a disability.

Accessibility design benefits everyone

Inclusive design includes people with disabilities. So accessibility is a natural outcome of effective inclusive design.

And accessible design can also benefit people without disabilities, making products inclusive of more people.

Let’s take an example from the physical world first: accessibility curb cuts.

Curb cuts (or ramps) can make pedestrian crossings and walkways accessible to wheelchair users or other people who may struggle with high curbs.

Accessibility ramps also benefit people without disabilities, such as people pushing strollers, carts, or other wheeled objects. If you’ve ever dragged heavy luggage across streets on your way to a train station or the airport, for example, then you too are likely to have experienced the benefit of accessibility design.

Many digital accessibility features benefit people without disabilities, too. A good example of an accessibility feature used by people without disabilities is: captions.

Captions are an accessibility feature that is required to make video content accessible to people with hearing disabilities. But their benefits extend far and beyond.

Captions are useful to many people in varying situations and environments:

- they are needed by people who are deaf or hard of hearing

- they are used by non-native speakers to aid in comprehension

- they are preferred by many people who comprehend written words better than audio

- they are used by someone working in a quiet or a noisy place (such as a library, a coffee shop, in a nursery with a sleeping baby, or in a meeting!)

- they are used in public places such as airport or airport lounges where TVs and videos are muted by default, and rely on captions fully

- they have also been particularly useful in times of COVID as many conferences went online and talks were given by speakers with low-end microphones or spotty wifi, making non-trivial portions of their talks difficult to understand

And there are many more day-to-day contexts in which people will benefit from reading captions and subtitles.

Captions and transcripts are but one of many accessibility features that are beneficial to all people.

High contrast display modes are also an accessibility feature that makes digital content more usable for all people. Someone working on their phone or computer outside on a sunny day may increase the contrast of the display to increase its readability.

I could go on and on about examples of accessibility features that are used on a day-to-day basis not only by disabled people but by those who are not.

All this means that accessibility requirements also benefit people and situations that are the target of inclusive design. But keeping accessibility focused on disabilities encourages research and development on the specific needs of people with disabilities, and solutions that are optimized for these specific needs.

Most accessibility requirements also make Web content more usable by more people.

Accessibility vs Usability

There’s a lot of overlap between accessibility and usability, but they are not the same.

The International Standards Organization (ISO) defines usability as the “extent to which a product can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals effectively, efficiently and with satisfaction in a specified context of use”. (emphasis mine)

In other words, usability design should support diverse users in their diverse contexts to accomplish their tasks with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction.

Usability practice and research may not specifically target the needs of people with disabilities, but it could address accessibility when:

- “specified users” includes people with a range of disabilities, and

- “specified context of use” includes accessibility considerations such as assistive technologies.

So accessibility design targets the needs of people with disabilities. Inclusive design targets the needs of a diverse group of people, including people with disabilities. And usability design is the extent by which users are enabled to achieve their goals effectively, efficiently, and with satisfaction.

By narrowing the definition of usability design to focus on users with disabilities, we could say that usability design must ensure that products are usable by people with disabilities.

Accessibility, on the other hand, does not always ensure that a product is usable. Not all accessible websites are usable. You can have an accessible website that is completely unusable.

When we say that a website is accessible we usually mean that it complies to standard accessibility requirements and that the content can be programmatically accessed. But how effectively and efficiently that content can be accessed determines how usable it is.

Users need to be able to do things quickly and efficiently. And they need to feel satisfied with the results. You may have a technically-accessible site that is a nightmare to use.

The only way to make sure something is usable is by observing people succeed in using it.

To ensure a site is usable, you should conduct usability tests that may uncover difficulties or possible barriers your users are facing that are making their experience inefficient, and then address those issues in your design and implementation.

For example:

- do you have dozens of links and repeated content on pages and no quick way to skip over them?

- Is the way you’re loading your interface preventing the user from doing what they want as fast as they want to?

- Do all controls have clear and visible labels?

- How easy or difficult is it to perform certain tasks?

- Does everything work with keyboard as expected?

- Are users having any difficulty performing certain tasks because you’re using unexpected key combinations and interactions?

- Are your components easy to operate? or are they too complex?

Usability testing will help you find and uncover barriers to access that you may not have considered during your design and development process, so that you can come up with more inclusive solutions.

So accessibility implementation is the first step in making truly inclusive and usable products, and it should always be followed by usability testing.

“Think of accessibility as the lowest bar; it works with assistive technology, but to go beyond ‘it works’ to ‘it’s enjoyable and easy to use’ you’ll need to test with real users.”

— Kate Kalcevich, Head of Services at Fable

Ultimately, both inclusive and accessible products need to be usable. Because how inclusive and accessible are they really if they can’t be used by the people they were designed for?

Back to accessibility. :)

Accessibility is about removing barriers to equal access for people with disabilities.

There is no accessibility design or accessibility development without disabilities.

We can’t design and develop for accessibility without knowing more about what and who we are designing for. In the following sections, we’ll learn more about the different types of disabilities, and how people with disabilities access the Web.

The different types of disabilities

There are many different types of disabilities, and they usually fall under one of these 4 types of categories:

- Visual disabilities, which include any kind of vision loss, such as blindness, low vision, cataracts, glaucoma,…

- Hearing disabilities, such as deafness, or loss of hearing caused by age, loud noises, or an infection, among other reasons

- Mobility disabilities, such as paralysis, amputation, muscular dystrophy, arthritis, a spinal cord injury,…

- Cognitive and learning disabilities, such as attention deficit, dyslexia, memory loss, brain injury,…

Some disabilities are visible (such as loss of limb); other disabilities are invisible—they are not visible from the outside, yet they can limit or challenge a person’s movements, senses, or activities. Vestibular disorder is an example of an invisible disability that can cause physical sickness (feeling of dizziness, vertigo, nausea and vomiting) and can be triggered by irresponsible use of Web animations. (Yes, Web animations can literally make people physically sick.)

Some people are born with permanent disabilities that fundamentally change the way they perceive the World — and, by extension, the Web. Others acquire permanent disabilities after they are born. Other people might be browsing the Web with a temporary disability caused by an accident or a temporary health situation. (Disabilities can frequently come with fatigue, chronic pain, and inability to focus, for example.) And there are people who are limited by situational disabilities like being in a noisy room or in a low-lighting condition.

Over 1 billion people around the world living with some form of disability. It is estimated that one in five people have a permanent disability, but 100% of the population will be faced with vision, hearing, motion, or cognitive disabilities at some point in their lives. After all, we’re all just temporarily abled.

(— Cindy Li)

Anyone could be living with a kind of disability on any day, that might be caused by an accident or by their current environment.

This means that when you’re designing and developing for accessibility, you’re making your product accessible to everyone—even those that you would normally not consider to be disabled. Your entire user base will benefit from accessibility. Your future self will, too.

The word “disability” is not bad but instead describes a state of being that we may experience situationally, temporarily, or permanently, perhaps due to social or medical circumstances. […] many of us benefit from accessible design, even when we don’t identify as having a disability. […] Accessibility benefits every single human being on this planet, disabled and abled.

— Anna cook, Senior Accessibility Designer

Being aware of various types of disabilities is important when designing for accessibility. But to start get more practical, we need to be aware of how someone with a disability may access and use our products, because accessibility design and development considers the wide range of technologies that people use to extend their capabilities.

So, how does someone with a disability access the Web?

When a person has a disability, they might find it difficult to access, perceive, understand, or navigate the Web. As such, they use Assistive Technologies to assist them in doing so.

What is Assistive Technology (AT)?

Assistive technology (which we will refer to as AT moving forward) is technology used by individuals with (varying levels and kinds of) disabilities in order to perform functions that might otherwise be difficult or impossible. It is an umbrella term for a wide variery of tools, including tools that enable access to information on the Web.

Despite the word “technology”, not all AT is high-tech. A wheelchair is an example of assisitive technology. Hearing aids are assistive technology. Eyeglasses are a form of assistive technology that many of us use. An example of a super low-tech assistive technology is a pencil grip.

Keyboards, screen readers, braille displays, voice recognition software, switch controls, and screen magnifiers are examples of high-tech assistive technology. Operating system and browser accessibility display modes (such as dark mode, and Windows High Contrast Mode) are also a form of assistive technology. This variety of ATs are available to enable users to access the Web in the manner they prefer.

This means that users accessing the Web might:

- use a keyboard instead of a mouse,

- change browser or OS settings to make content easier to read,

- use a screen reader to ‘read’ (speak) content out loud,

- use a screen magnifier to enlarge part or all of a screen,

- use voice commands to navigate a website

A tremendous variety of assistive technology is available today, providing the opportunity for nearly all people to access digital information. This means that people browse the Web in a wide variety of ways and using various types of tools. Many people will also have accessibility features enabled when they do. For example, they may have dark mode enabled, or be using high contrast mode, or have chosen a larger font size.

It’s practically impossible to predict all the ways your visitors may choose to browse your website or use your product.

Furthermore, people might use more than one AT at a time. There are people who navigate the Web using on-screen keyboard, mouse headband, and voice recognition software at the same time.

Accessibility design and development considers the wide range of AT that people use to extend their capabilities.

Understanding how people with disabilities browse the web using assistive technologies is critical to designing and implementing accessible and inclusive products and services.

We’ll see examples of people using AT throughout the course. You can’t take a course and go ahead building accessible products without getting to know more about the users you’re building for and how they access the web! And we will use some assistive technologies as we explain accessibility concepts in some chapters.

But if you’re not familiar with common ATs, or if you are unsure how people with disabilities use common ATs and you are curious to get some insights already (I hope you are!!), then I highly recommend taking a few minutes to watch the “Browsing with assistive technology” videos series by Tetralogical. This series “introduces commonly used software, who uses it, how it works, and ways people navigate content.”

There are five videos total, each less than 5 minutes long. So it’s a short and sweet, yet insightful, series of videos. Pause this video for 15 minutes and watch these videos. I’ll wait. Once you’re back, we’ll continue with the remainder of this chapter.

Assistive technologies don’t guarantee access

People with disabilities use AT to extend their capabilities, but an individual’s having proper assistive technology is no guarantee of having access. A person may be using assistive technology and still facing barriers to access.

The ability to access the Web is dependent on accessible design and the accessible implementation of that design. It is dependent on our work as designers and developers. It is our responsibility to remove barriers so that disabled people can access the Web, regardless of what they choose to access it with.

It should be clear at this point that Web accessibility is therefore about more than making a site work with screen readers.

We’ll mention quite a few ATs in this course, and you’ll learn how to design and write code in a way that makes your product accessible to as many of them as possible. We’ll focus on some ATs more than others — such as screen readers, voice controls, keyboard (and keyboard-like), as well as forced color modes.

Simulating disabilities is not enough

In a survey of Web Accessibility Practitioners conducted by WebAIM in 2021, 70% of accessibility practitioners and testers reported having no disability. While the survey notes that the percentage of respondents with disabilities increased to 29.1% in this survey from 26.4% in 2018 and 21.8% in 2014, suggesting that the disability diversity in the field is increasing over time, it may also be an indication that not enough people with disabilities are involved in designing, building, and testing for accessibility.

No matter how experienced you are with assistive technologies and how many accessibility techniques you implement, nothing will replace working and testing with disabled users who use these technologies on a daily basis. You cannot simulate some types of disabilities, so it will be difficult if not impossible to predict how all disabled users access the Web.

You can only confidently prove that something is accessible by observing people succeed in using it. So usability testing with users of assistive technologies is necessary to ensure your product or service is truly accessible.

A disabled screen reader user uses a screen reader in ways that are different to how a non-disabled person would use them. Someone who can see will most likely not use a screen reader the same way someone who is legally blind does. There will almost always be the bias of being able to see.

In her article How to avoid Twitter’s latest accessibility mistakes, Sheryl Byrne-Haber, a wheelhair user and disability advocate, says:

anyone can zoom a screen to 400 %, but without the lived experience of someone with vision loss, they won’t use the 400 % zoomed data the same way I do.

She goes on to note that:

You can pretend that you can’t see, can’t hear, have a hand tremor. It won’t give you the same results as testing with a person who is not pretending, but it should at least get some if not most of the barriers removed.

Speaking of removing barriers…

In order to design and develop for accessibility, we need to have some standard or universal guidelines to, well, guide us.

If you pulled up your website today and decided to make it accessible, where do you start? If you say: “I want to make sure people with disabilities can use this website”, where and how do you start?

If you want to start creating accessible products, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines is where you need to start. And the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines is what we’ll dive deep into in the next chapter.

So, I’ll see you in the next chapter.

References, resources, and further reading

- How People with Disabilities Use the Web

- What is AT?

- Accessible Design vs Inclusive Design

- Accessibility, Usability, and Inclusion

- a11y is web accessibility

- a11y = accessibility

- Web Accessibility for Newbies

- Is ‘a11y’ our ally? Thoughts on a tag for web accessibility

- We’re Just Temporarily Abled Designing for the Future

- Embracing design constraints

- WebAIM 2021 Million survey results and critic

- What is Shift Left Accessibility Testing

- The little book of accessibility

- Designing Safer Web Animation For Motion Sensitivity

- No accessibility without disabilities

- The “Browsing with assistive technology” videos series